Independence

Thunders In

Independence

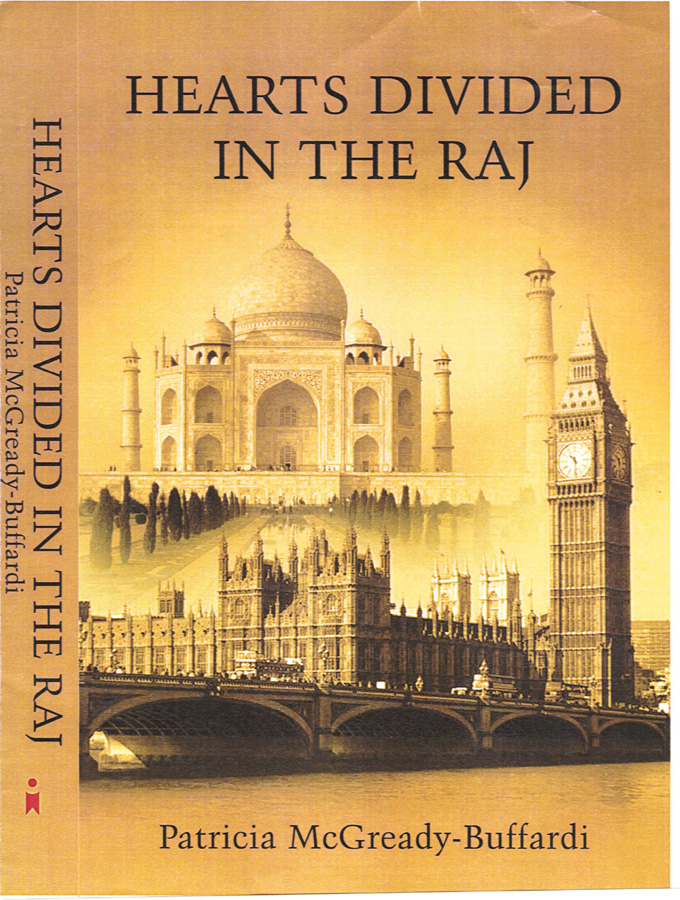

Thunders In When freedom from colonialism finally arrived at Midnight, 15 August 1947, the once vast subcontinent was refashioned, severed in three, with India at center stage and West and East Pakistan in the wings. But Independence was certainly not well received by us "mixed-breeds," with the blood of two nations in our veins. Descending upon the Anglo-Indian communities like an avenging angel, Independence and partition swept away any and all sense of security we ever had, and we lay low for a long time. Inevitably, the decision of the British to relinquish the subcontinent left Anglo-Indians afraid and ready to flee and, for months, prior to the changing of the guard, panic and terror gripped the Anglo-Indian communities all across the peninsula. In Bombay, we wept as our friends and relatives departed to Britain, Canada, Australia or New Zealand. Sadly, fear forced many heart-wrenching decisions, splitting thousands of families apart as some departed and others stayed on. No matter what the colour of their skin, though, white or swarthy, tan or coffee-brown, the exodus of "mixed-breeds" had begun. For my part, the colour of my skin was getting less bothersome since, growing up in colonial India, I had already found a devious way to enjoy a delicious concoction of both societies, British and Indian, jumping the prickly fences of both camps, at whim, and flirting with the two diverse cultures I had inherited.

But, during the final push towards Independence, my own family's tropical days and nights were filled with anxiety. Again and again, in the midst of all the turmoil, my father quelled our wavering minds, constantly reminding us, "We're staying. Remember children, you were all born and raised here. India is home." It was certainly okay for him to speak in favour of staying on for he, and we, his brood of three were Anglo-Indians. But Mummy was not and, even after all these years, her words reverberate in my ears, "I have not one jot of Indian blood in me. What's going to happen to me?" A Domiciled European, my mother feared the worst, arguing in favour of the family going to live with some of her relatives who had never set foot in India. Conversely, born and raised in India, she had never set foot on British soil, her kin in touch only via the boat mails. Once again, Daddy announced that no one was to ever talk about leaving the country. He warned us, though, that there would be many more sad days ahead as other friends and relatives departed. He cautioned us to be pleasant to the servants and never to do anything that would cause them to turn on us. We were not to side with either our British or Indian playmates and, more importantly, to stay neutral when our Hindu and Muslim friends quarreled. I soon realized that my father's decision to remain in India was absolute. Fortified by his infectious optimism, as he tried to pull us through the strong currents of pessimism, I probably irked all my young Anglo-Indian friends who were getting ready to sail to London. And yet, in the innocence of childhood, my rather brash statements paled in comparison to some of the others flying around the compound. "My Daddy says you will hate the snow and ice in England," I hollered from my second-storey window, since I was quarantined with chicken-pox. "Everyone is so pale and sickly over there," I taunted, hoping against hope that my little friends would change their minds and not leave the beehive at Dhun Raj Mahal. But I had never seen snow when I made my hearth-wrenching comments and knew not how lovely the English springs and summers could be, although I had heard those statements about pale faces often enough to include them in my everyday speech. At the drop of a hat, I defended the land of my birth.

Actually, in the late 40s, the principal fear of most Anglo-Indians was fear of retribution. People who, like my grandfather and great-grandfather, had been steadfast and loyal to their British employers, continuing to man the stations, trains and telegraph offices, while their Indian staff joined the hartals, strikes. Anglo-Indians, given preferential treatment by the colonialists, were suddenly caught between a rock and a hard place. Although most Anglo-Indians could speak a smattering of Hindi, Tamil or Bengali, when Independence knocked on the door hardly any of us could read or write in the vernacular. Emulating the cultures and religions of our Western ancestors, in preference to those of our Indian ancestors, Anglo-Indians damned the British for departing India. And Grandpa was no exception, inferring, as most Anglo-Indians of his generation did, that it was impossible to live without the British when indeed they had already been doing so, as they were constantly looked down upon by the mightier-than-thou settlers and simply tolerated in preference to the natives. But when one's livelihood is dependent on the rulers it is hard not to play by their rules.

As if the riots and murders amongst Hindus and Muslims were not enough, the deities joined forces to punish the country further. The Monsoon arrived. As thunder rumbled across the charcoal black sky, cloudbursts continuing for days, the deluge brought life to an absolute standstill in Bombay. All plans were aborted as umbrellas flew up and away like big black butterflies. But the news that traffic was snarled was music to my ears: school would remain closed for several days. Even rickshaws were forced to stay off the city streets. For those of us who usually walked to school our gum-boots or galoshes would have been totally submerged and, even if the convent had not closed its doors, our mothers simply would not have allowed us to venture forth. But, I will never forget the Monsoon air, pregnant with alternating bursts of hot or cold breezes, rather like two faucets fighting for control in the same bathtub. Suffering the indignities of prickly heat in the sweltering cauldron of Bombay, I scratched and scratched until the surface of my skin bled.

The month of June was tyrannical. When it rained

in Bombay days and nights melded like dark pewter; the rain thrashed the

windows; the wind howled like a wounded animal. Alas, the Monsoon was

devious, receding graciously, from time to time, giving us mortals just

enough time to come up for air and to witness its aftermath. The city

was under siege. Oppressive, wet heat, like a mortal enemy dealt a blow

by blow attack, reduced one's status to that of a helpless baby. Afterwards,

it was sad to witness the damage: the mangled roofs; the splintered window-shutters,

lifted off their perches like feathers in the wind; the horizontal trees;

the lampposts, twisted and gnarled; the dangling tram cables; the abandoned

stalls and market-places; people wading everywhere; bodies and bundles

huddled together under every arch or doorway. The homeless. But, like

Shiva, the most important Hindu God, the monsoon was both a destroyer

and creator, hurting and cleansing the city at the same time.