As if to make up for our soggy welcome two days earlier, Barkerville bids us farewell in brilliant sunshine. Beyond Wells, the gold rush trail leads to Cottonwood House estate, which literally straddles the historic Old Cariboo Road. Like Hat Creek House, this too was a hostelry and stagecoach stop for drivers, prospectors, and merchants who needed to stock up on provisions and rest overnight while saddlery and wheels were repaired. Owned by the Boyd family from 1874 to 1951, Cottonwood House is a jewel in the treasury of the Cariboo region's heritage homes. Meticulously restored rooms are set with antique furniture, ornaments, photographs, silverware, and crockery, and it is easy to 'hear' again the clink of glasses and hum of conversation in the large dining room as guests gather for a meal.

|

I am regretful that time doesn't permit a visit to the rustic log guest cabins dotted around the estate, or the opportunity of looking in on the farmyard poultry and animals—or even to browse through the collection of heritage wood products offered for sale. But that said, there's no better reason than missed opportunities, to return another day!

I probably wouldn't remember much about our next stop at Quesnel, if it wasn't for Mandy. She lives in the Museum, and is far from being pretty—in fact her face looks like that of an abused child. And perhaps, like a child who has suffered cruelty, she is vindictive. For one thing, sitting in her glass case with her frilly doll's bonnet framing her cracked face, she has been known to turn her head away from a camera's intrusive eye. For another, she has caused immeasurable grief to photographers who have tried to capture her image: they've had to deal with messed up development equipment, and in one instance, the destruction of a video camera hopelessly jammed with snarled video tape. Time and again negative film has turned out to be blank. Her previous owner was relieved to get rid of the eighty-year old doll, after hearing intermittent wailing sounds and cold winds (at the height of summer) whirling through the house. I peer at Mandy, who looks stony-eyed past me, but my digital camera remains out of sight. No sense in risking a hard-drive crash when I start downloading my travel shots onto my desktop.

As Brent hits the back-roads beyond Quesnel, we are once again on a twisting trail, following the Fraser River, far, far below us, with walls of evergreen forests rising from the river's edge, and reaching up into a cobalt blue sky. There is little traffic, other than the occasional logging truck, and the air smells of earth and grass. A lone eagle circles a distant peak. Conversation dies away, and the only sound is the thrust of the diesel engine as we climb and dip around corners.

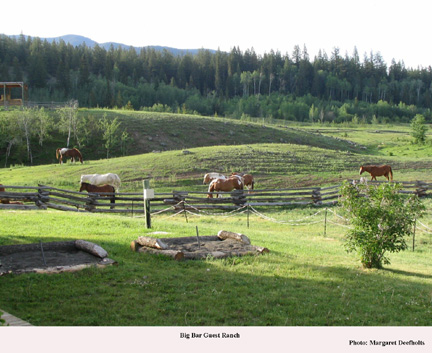

One

of the highlights of a trip such as this, is staying overnight at a typical

Cariboo ranch. Big Bar Guest Ranch sprawls across undulating country,

against a backdrop of mountain ranges smudging the horizon. I stand out

on the patio in the crisp morning air, a mug of freshly brewed coffee

in hand, and listen to the whinny of horses in the surrounding paddocks.

Drawn back into the dining hall by the smell of sausages, bacon, and fried

eggs, it is hard to believe that just the night before, after a country-style

dinner of immense proportions, I thought I'd never be hungry again!

One

of the highlights of a trip such as this, is staying overnight at a typical

Cariboo ranch. Big Bar Guest Ranch sprawls across undulating country,

against a backdrop of mountain ranges smudging the horizon. I stand out

on the patio in the crisp morning air, a mug of freshly brewed coffee

in hand, and listen to the whinny of horses in the surrounding paddocks.

Drawn back into the dining hall by the smell of sausages, bacon, and fried

eggs, it is hard to believe that just the night before, after a country-style

dinner of immense proportions, I thought I'd never be hungry again!

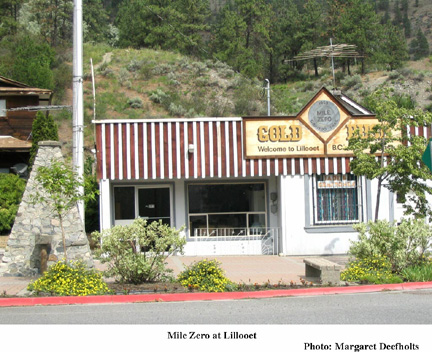

The back road from Big Bar Ranch meanders past fields

of riotous wild flowers, and then, heading towards Lillooet, we once again

we emerge onto the highway edging the Fraser River. The town lies along

an earlier route to Barkerville, (before the construction of the Old Cariboo

Road) which snaked up from the north end of Harrison Lake  via

Port Douglas. All the way along our route through the Fraser Canyon I've

noted the mile markers (used as an aid to stagecoach drivers who had to

stop along the way to change horse teams) but now, at Lillooet we are

at Mile 0. This was the starting point in terms of distance measurements

and roads radiated outwards towards the Cariboo (and Barkerville), or

in the reverse direction towards Pemberton.

via

Port Douglas. All the way along our route through the Fraser Canyon I've

noted the mile markers (used as an aid to stagecoach drivers who had to

stop along the way to change horse teams) but now, at Lillooet we are

at Mile 0. This was the starting point in terms of distance measurements

and roads radiated outwards towards the Cariboo (and Barkerville), or

in the reverse direction towards Pemberton.

The

“Bridge of 23 Camels” across the Fraser River into Lillooet

commemorates a quirky little anecdote of gold rush history. Frank Laumeister,

a prominent Victoria merchant and packer, came up with the idea of introducing

camels as pack animals to transport goods along the trail. A camel could

carry twice as much, and travel twice as far, as a mule, and if these

animals worked well in desert territory, well why not along the gold rush

trail too? Fine in theory; a disaster in practice. The 300 camels purchased

from the USA were healthy animals, but their hooves couldn't deal with

the rocky terrain, plus they spat, bit, and kicked everything within sight.

Worse still, when they were in heat, the overpowering smell drove all

the other pack animals into a mad stampede. Eventually the camels were

either auctioned off or turned loose into the wild.

The

“Bridge of 23 Camels” across the Fraser River into Lillooet

commemorates a quirky little anecdote of gold rush history. Frank Laumeister,

a prominent Victoria merchant and packer, came up with the idea of introducing

camels as pack animals to transport goods along the trail. A camel could

carry twice as much, and travel twice as far, as a mule, and if these

animals worked well in desert territory, well why not along the gold rush

trail too? Fine in theory; a disaster in practice. The 300 camels purchased

from the USA were healthy animals, but their hooves couldn't deal with

the rocky terrain, plus they spat, bit, and kicked everything within sight.

Worse still, when they were in heat, the overpowering smell drove all

the other pack animals into a mad stampede. Eventually the camels were

either auctioned off or turned loose into the wild.

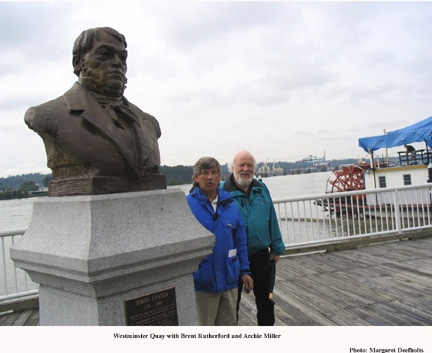

Beyond Lillooet, lake vistas open up—irresistible

to photography buffs—and we are on the home stretch via Pemberton

and Whistler to Vancouver. The ghosts of history have ridden alongside

me through the trip, and now in New Westminster, only one more remains

to bid me farewell. In some ways, he is the most important of all. I stand

near his bronze statute at the New Westminster quay, watching the swirl

of the river which bears his name, thinking about the story which began

at this spot almost two centuries ago when he arrived here to open up

a fur trading route to the Pacific. He is Simon Fraser, intrepid explorer,

adventurer, and founding father of the Province of British Columbia. The

year was 1808. By 1827 the Hudson's Bay Company had set up a lucrative

trading post at Fort Langley, several miles up-river. The stage is set

for Don McLean, and the Indian who handed him a bag of gold dust. My journey

has come full circle.

|