We

veer off the highway at Lac La Hache, onto a gravel back road snaking

through true Cariboo country—rolling meadows fringed by cottonwood

trees and ranches bordered with distinctive Russell split-rail fences.

Free range cattle saunter across the path, and a moose in the shadow of

a clump of evergreens freezes into startled immobility.

We

veer off the highway at Lac La Hache, onto a gravel back road snaking

through true Cariboo country—rolling meadows fringed by cottonwood

trees and ranches bordered with distinctive Russell split-rail fences.

Free range cattle saunter across the path, and a moose in the shadow of

a clump of evergreens freezes into startled immobility.

We are on the fringe of Horsefly and Likely, both small towns with a big chunk of gold rush folklore tucked into their yesterdays.

As the Fraser River gold rush began to fade, some prospectors headed for home. Others like Peter Dunlevy, Tom Moffitt, Tom Manifee, Jim Sellers, and Ira Crow figured that the gold dust washed down was an indication that a richer mother lode of precious ore lay further into the Cariboo.

According to an article written by Sage Birchwater—a writer living in the West Chilcotin—and published in the Cariboo Sentinel Vol II, at some point along their journey up river, Dunlevy and his group encountered a Shuswap Indian, Tomaah. The Indian looked on curiously while Dunlevy panned gravel in a wooden sluice box. “Why you wash stones?” He asked. When Dunlevy talked about gold, Tomaah shook his head in puzzlement, so from the bottom of his rocker, Dunlevy held out a fleck of gold. It was approaching dinner time, so the group invited Tomaah to join them. At the end of the meal, his face lit by the flicker of a campfire, the Shuswap went back to the subject of gold. He was contemptuous of the dust the men were laboriously sifting from the river bed and offered to show them where to find big shiny stones. How big? Tomaah flicked a bean off his plate: “That big!” He said. His words caused an uproar among the prospectors. A stunned Dunlevy questioned Tomaah further, and the man drew a rough map in the sand. Before parting company, the prospectors agreed to meet the Indian near Lac La Hache.

Fortified with fresh provisions, they headed for the rendezvous, arriving in time for a big tribal celebration of sports and contests. The next evening, true to his word, Tomaah appeared, and with him was his friend, Long Baptiste. But all was not well. The party of white men was not welcomed by all the bands, many of whom were suspicious and hostile What had started out as a sports contest unexpectedly developed into a council of war. Dunlevy and his group hung on the edge of uncertainty. Were they about to be massacred, their bodies flung into the thick woods and forgotten? However, reason prevailed as the Shuswap and Yabatan chiefs pointed out that the fur trade at Hudson's Bay had proved lucrative to them in the past, and it was obvious that the white men had superior fire power. Rather than precipitate a war that would only result in loss of their people, it was best to reap the benefits of co-operation. It was a turning point in the history of the Cariboo gold rush.

Unlike the Agnes McVea tale, this one had a happy ending.

Baptiste led them up to the Horsefly River and, although there is no formal record of how much gold Dunlevy's party

took out of the area, it is estimated that they cleared over a million

dollars in today's currency. Baptiste on Dunlevy's recommendation became

Judge Begbie's personal travel guide and companion.

and, although there is no formal record of how much gold Dunlevy's party

took out of the area, it is estimated that they cleared over a million

dollars in today's currency. Baptiste on Dunlevy's recommendation became

Judge Begbie's personal travel guide and companion.

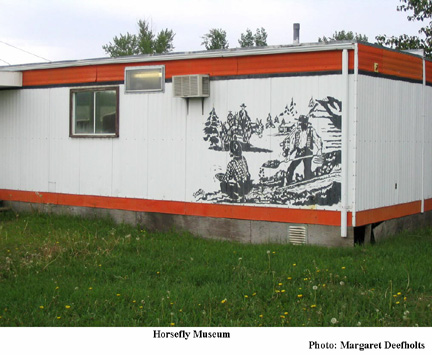

Both Horsefly and Likely doze in the afternoon sun, as we stop briefly to look at the Horsefly River where Dunlevy and his group once made their fortunes. The waters no longer hold any shiny nuggets, but later in the year they will shimmer coppery red as sockeye salmon seethe past fly-fishing enthusiasts drawn here, much like the prospectors over a century ago, but with a different haul to cache!