|

BATTLE ROYAL

My family and I are in Sussex, England. It is a glorious summer morning with a light breeze playing through the trees. We are on a knoll, and beyond the slope is a tranquil Constable landscape: a field cross-stitched by hedgerows, which merges into distant woodland. The only sounds are chittering sparrows, and the far-off rumble of traffic floating up from a thread-like highway.

William of Normandy was getting the worst of it. The Saxons had the advantage of being positioned on the hill (where we now stand), while the Normans on the field below were being steadily pushed back. It was mid-afternoon, and a group of Saxons attacked a flank position, chasing the fleeing Normans with whoops of “Ut, Ut,” (“Out, Out”) and “Gutemite” (“God Almighty”). In desperation, a small group of Norman soldiers unexpectedly turned around to defend themselves. The Saxons, unable to run uphill fast enough to get back to their own lines, were slaughtered en route. As the day wore on, both sides were exhausted. It was time to take stock and nibble on some refreshments. “Tea time chaps!” (or the equivalent!) brought about a mutual lull in hostilities. That’s when William of Normandy came up with a brilliant idea. The earlier flank attack had ended in disaster for the Saxons. What if the entire army feigned retreat? The Saxons would, no doubt, pursue them, and once lured onto a “level playing field” (so to speak) the Normans could then do an about-face—and fight to the death. t worked. King Harold, pierced in the eye by a stray arrow, lay dead on the battlefield, following which Saxon morale collapsed, and William of Normandy became king of England. He was the last invader ever to successfully occupy Britain.

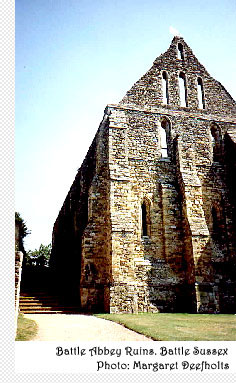

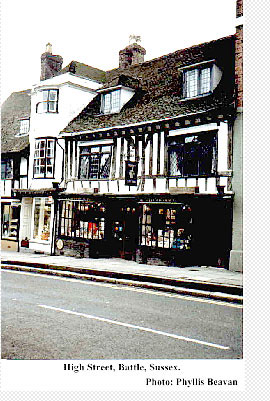

Henry VIII, who had scant patience with the Abbey’s significance, all but destroyed it in his drive to eradicate Catholicism in England in the 16th Century. With the dissolution of monasteries, the Abbey church was reduced to skeletal walls and we pause to read a slab at the site of the original High Altar which marked the actual spot where the Saxon King was slain. The ancient Cloisters and Dorters in the Abbey grounds, where the monks once had their living quarters and dormitories, still has an aura which makes for hushed conversation. Battle’s market square outside the Abbey grounds is busy and we decide to “slake our thirst” at a medieval pub, “Ye Old King’s Head” whose signpost has an artist’s impression of an impressively moustachioed King Harold. Over a pint and a ‘ploughman’s lunch’ a group of local “regulars” strike up a conversation with us. They are regretful that we have missed the big event of the year—the two week Battle Festival, held either at the end of May or in early June.

Another one adds, “And you can listen to concerts, come to poetry readings and watch plays....” "And see the Maypole dancers. And jousting tournaments. ” interrupts a third. “You don’t have that in Canada, do you?” No, we probably don’t. And, therefore, what better excuse can there be to return another time? Perhaps next year—when Battle, the site of Britain’s most profound historical event in this millennium, celebrates its past—and looks towards its future over the next thousand years. |

| Margaret Deefholts August 30, 1999 |

|

What

could be more typically British than ‘a cuppa tea’? And, almost

a thousand years ago a break for tea (in a manner of speaking!)

changed the course of English history.

What

could be more typically British than ‘a cuppa tea’? And, almost

a thousand years ago a break for tea (in a manner of speaking!)

changed the course of English history.  Scroll

back to 14th October 1066. The field in front of us was in turmoil.

Norman archers spewed arrows, Saxon battle-axes flashed murderously

and the thunder of cavalry hammered against the consciousness

of the wounded and dying.

Scroll

back to 14th October 1066. The field in front of us was in turmoil.

Norman archers spewed arrows, Saxon battle-axes flashed murderously

and the thunder of cavalry hammered against the consciousness

of the wounded and dying. Today,

Battle, the actual site of the conflict, is a small hamlet, about

ten miles north of the better known town of Hastings. Massive

entrance gates with crenellated towers leads onto this, one of

England’s most significant historical sites. We explore the

ruins of Battle Abbey, built by William the Conqueror in celebration

of his victory or (depending on who you talk to) in atonement

for the thousands of soldiers slain on the battlefield on that

fateful day in October 1066.

Today,

Battle, the actual site of the conflict, is a small hamlet, about

ten miles north of the better known town of Hastings. Massive

entrance gates with crenellated towers leads onto this, one of

England’s most significant historical sites. We explore the

ruins of Battle Abbey, built by William the Conqueror in celebration

of his victory or (depending on who you talk to) in atonement

for the thousands of soldiers slain on the battlefield on that

fateful day in October 1066. “It’s

a grand time to visit.” One of them says . “People dress

up in medieval costumes. There are jugglers and street musicians

and everyone has a jolly good time.”

“It’s

a grand time to visit.” One of them says . “People dress

up in medieval costumes. There are jugglers and street musicians

and everyone has a jolly good time.”