The Streets of Mumbai aka Bombay

Margaret Deefholts

If the streets of any city can be said to reflect its character, then Bombay would win hands down as the most clamorous and colourful metropolis in the world. Nothing can compare to the relentless turmoil of a city with a population of more than eighteen million, give or take a few hundred thousand transients who fall through the mesh of official statistics. Coarse, gritty, at times horrifying, it is a city where the extraordinary becomes the commonplace, and the commonplace no longer exists except as a paradox.

Bombay-ites are wryly amused when visitors are stunned into disbelief at the swarms of commuters who swarm the city sidewalks each morning. They look nonplussed when asked about the thousands of destitute living in tin and tar shacks along the footpaths, who eat, sleep, procreate, excrete, bathe, beg, steal, haggle, weep and dance on the pavements. They wag their heads in agreement that the sidewalks are all but impossible to walk on because they are crammed with unlicensed vendors' stalls, stray cows, mendicants and vagrants. “Well of course,” they shrug. “That's Bombay . Humid, congested, filthy and noisy. It's always been that way and nothing and nobody is ever going to change it.”

It hasn't always been that way, of course. Although hard to believe, Bombay — now called by its original name of Mumbai—was once just a group of fishing villages on a cluster of swampy islands. In 1661 it was transferred from the Portuguese to the British as part of Catherine of Braganza's dowry when she married King Charles II. Today it is the sub-continent's most industrialised city, with a veneer of sophistication overlying a seamy underside of poverty and crime. It boasts the largest and glitziest film industry in the world and it has the dubious distinction of being home to Dharavi, a huddle of tin and tar shacks situated on a stretch of stinking marshland—inarguably the worst slum in Asia.

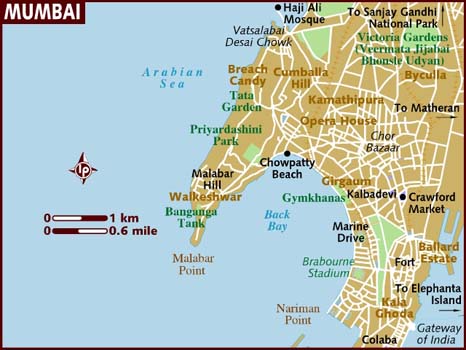

The city built along the west coast of the Indian peninsula is elongated and runs north-south. The original islands have been fused by extensive land reclamation, and although these areas are still called “causeways”it would require a considerable stretch of imagination to see them as once being part of the surrounding ocean. They are heavily built up and thickly populated.

At the south end lies “Colaba Causeway” a busy road, flanked by commercial establishments, restaurants and shops. Fabrics—shimmering silk, gold-thread encrusted brocade and dazzling printed cottons—is sold by the metre. The shops' tailors will whip up made-to-measure garments within a matter of hours. Further along are shops with mezzanine upper floors where helpers scurry around pulling shoe boxes from stock. These are stacked, sometimes as many as six deep, and hurled down to salesmen who grab them intact in mid-air. No records exist of unwary customers who have been brained insensible by these missiles.

Colaba Causeway's pavements are too narrow and uneven to accommodate shanty-dwellings, but even so pedestrians squeeze by vendors' trolleys stacked with imitation jewellery or ready-made garments, sellers of cold drinks and peanuts and itinerant pedlars who dangle hideously gaudy trinkets and plastic toys at passersby. It has its quota of beggars too, and accommodating one of them will cause a shoal of others to materialize within seconds. To move beyond the forest of outstretched palms is to run the gauntlet between conscience and expediency—while satisfying neither.

East of Colaba Causeway, and running parallel to it is the road flanking the harbour. It leads to the Gateway to India , a massive arch erected in 1911 to celebrate the visit of George V and his consort Queen Mary. To the left is the Taj Mahal Hotel. Step inside and you are abruptly juxtaposed into a world of monied elegance. But on the street, snake charmers and street acrobats vie for tourist dollars, and in the shadow of the archway, some of the city's homeless cook their humble afternoon meals on kerosene stoves. Beyond the sea wall, the ocean glints steely-blue under a merciless noon-day sun.

Moving further north to Flora Fountain (also known as Hutatma Chowk) is to be at the hub of the downtown city scene. The traffic is chaotic, and incredibly the sidewalks are even worse. Yet, flanking the melee of people, the blare of car horns and the raucous calls of hawkers, are dignified stone buildings, built at the heyday of Empire, which house some of the city's most prestigous business establishments. Broad streets run like spokes of a wheel from Hutatma Chowk; one runs westward to Churchgate and from thence westward to the sweep of Marine Drive , another goes north towards the Gothic edifice of Victoria Terminus station.

Churchgate station and Victoria Terminus station funnel commuter trains into the city and they are the setting for an activity that is unique to Bombay 's life-style. Every working day around noon eighty or more men, wearing peaked white caps, fan out from both stations, pushing ahead of them enormous wooden trolleys each stacked with roughly sixty metal containers. These are the dabba-wallahs of Bombay , and they deliver hot, home cooked meals to their clients at offices throughout the city centre. The tiffin carriers (or dabbas) are insulated cylindrical metal containers with compartments holding rice, vegetables, lentils and desert, and have been collected three hours earlier from suburban households spread across a radius of fifty or more miles. These are loaded onto local trains, by the first set of coolies. The tiffin-carriers will be winnowed and sorted out for various destinations at one or more exchange stations en-route. The man at the end of the delivery line, could be the third or fourth handler in the web, and the astonishing thing is that neither he, nor any of the other coolies know how to read or write. A hieroglyphic code of dots and dashes painted onto the containers tell the handlers all they need to know about each containers destination and origin. After the lunch hour is over, the whole process is reversed, and the empty tiffin-carrier is delivered back to the house by late afternoon. For most office workers—particularly caste-conscious Hindus - paying around ten thousand rupees (about $200) per month for a home-cooked lunch, is cheaper and infinitely preferable to a restaurant meal.

Between Victoria Terminus and Crawford Market, the city's produce, fish and meat market, the sidewalks are home to some of Bombay 's open-air artisans. Superimposed on the noise of traffic, is the shriek of grinding wheels operated by knife-sharpeners, the hiss of welders irons, and the assorted tapping, rasping and shearing sounds of locksmiths, electricians, tire-repairers and bike mechanics working under the shade of dusty-leafed trees. A little further on, barbers shave customers squatting in front of them, with cutthroat razors. A haircut costs a few additional rupees. Next to them are ear-cleaners who dig and delve for errant globs of wax in their clients' ears. For those curious about what the future holds, palmists and readers of horoscopes are also open for business, their charts propped against the railings of an adjoining building. A nearby pan-beedi stall sells leafy packets of chewy betel-nut and small strong smelling Indian cigarettes, which can be bought singly and lit from a slow-burning rope hanging from the corner of the shop.

Fifteen minutes further along, is the Muslim area with its elaborate mosques and small restaurants selling spicy mutton rice-biryani and boti-kebabs. Women enveloped in black burqhas with a small lattice work opening for their eyes, haggle at wayside stalls or stand gossiping in groups.

The Bombay street-scene embraces the bizarre with nonchalance. It is not unusual to encounter groups of people dressed in swirling skirts and saris of bright orange, parrot green and peacock blue, wearing jangling anklets, bangles, rings, necklaces, earrings and nose-rings. These are not women. Square jawed with heavy eyebrows and stubbled beards, their faces are grotesquely caked with powder, lipstick, rouge and mascara. They are not transvestites either. They are Hijras - some of them are eunuchs who have submitted to voluntary castration, while others are hermaphrodites who are born with the characteristics of both male and female sex organs.

The Hijras are a society unto themselves. They live in their own settlements and can be found in all the major cities of India . Apart from prostitution, their main source of income is a ritual performance at weddings or more often, upon the birth of a male child. They turn up uninvited and demand to see the baby. The child is then crooned over, stroked and passed from one to another, after which they perform a ritualistic dance accompanied by a chant invoking blessings and good fortune. They are seldom turned away for, although outcasts, a Hijra's curse is a terrible thing to be inflicted on a boy-child, and families will pay lavishly with sweets and money, to ensure protection against their ill-will.

The Hijras are a society unto themselves. They live in their own settlements and can be found in all the major cities of India . Apart from prostitution, their main source of income is a ritual performance at weddings or more often, upon the birth of a male child. They turn up uninvited and demand to see the baby. The child is then crooned over, stroked and passed from one to another, after which they perform a ritualistic dance accompanied by a chant invoking blessings and good fortune. They are seldom turned away for, although outcasts, a Hijra's curse is a terrible thing to be inflicted on a boy-child, and families will pay lavishly with sweets and money, to ensure protection against their ill-will.

On the streets, they are bawdy and if denied alms, food or free passage on public transport, they clap and chant obscenities while lifting their skirts and flaunting their sexual organs to the chagrin of their victims. Shop-owners are anxious to have them move on, giving them free cigarettes, snacks or whatever else they happen to fancy. Most of the time their charity is rewarded with hoarse jeers, and ribald comments. Nonetheless these are preferable to incurring Hijra wrath.

Bombay 's red-light district is located in Kamatipura. One of the streets running through the area is Faulkland Road (possibly a refinement of the original name) and it is lined by closely built, mean-looking buildings. Red velvet or brocade curtains hang at the entrance doors. The small windows on the upper floors have vertical bars, which is why the brothels are commonly known as “the cages” of Bombay .

In the bright light of day, the area looks like any other neighbourhood with women devoid of make-up going about their usual tasks of shopping or chatting to their neighbours. But by night a different atmosphere prevails. Girls with flowers in their hair, garishly painted faces and wearing shiny satin, low cut blouses, peer between the window bars and beckon to passersby, while the madam of the establishment sits like a fat spider at the entrance doorway and muscular bouncers lurk in the shadows.

Most of these prostitutes are sold into the trade—many of them as children of ten or eleven—enticed from as far away as Nepal , in the expectation of finding respectable work as domestics. Once they reach Bombay , the girls ‘disappear' and become prisoners for life within the tightly controlled world of prostitution. The argument has been made that they are better off than the thousands of starving destitute on the city streets. Their children are communally cared for and they, themselves, are fed and clothed and have somewhere to live. In addition most of them get a small percentage of the take. Although prostitution is legal in Bombay and the cages are regularly visited by health inspectors and social workers, AIDS runs rampant through Kamatipura. The horrifying fact remains that many of these women will suffer an early and excruciating death, without having any choice or hope of escape.

Less sordid than Faulkland Road , but equally crowded are the narrow lanes that thread through Chor Bazaar. This ‘Thieves' Market' offers an amazing diversity of second-hand merchandise, much of it stolen and displayed with no questions asked or answered. Picking one's way through clusters of cud-chewing cows, roadside litter and hawkers, it is possible to track down unusual items such as old wind-up gramophones, antique furniture and bric-a-brac. Vociferous haggling is the norm.

Bombay 's Marine Drive , a curving promenade flanked by a sea wall comes alive at dusk. Heat-wearied citizens turn out by the hundreds to stroll and chat in the balmy evening breeze that wafts off the Arabian Sea . At the north end is Chowpatty Beach where flamboyantly painted stalls sell spicy bhel puri (a Bombay 's specialty), violently coloured cold drinks and silky smooth kulfi ice-cream. To sample any of it, however tempting, gives literal meaning to the phrase ‘intestinal fortitude'. Less hazardous is riding a camel along the sands, against a backdrop of an enormous, lurid sun dipping to the horizon.

Bombay 's Marine Drive , a curving promenade flanked by a sea wall comes alive at dusk. Heat-wearied citizens turn out by the hundreds to stroll and chat in the balmy evening breeze that wafts off the Arabian Sea . At the north end is Chowpatty Beach where flamboyantly painted stalls sell spicy bhel puri (a Bombay 's specialty), violently coloured cold drinks and silky smooth kulfi ice-cream. To sample any of it, however tempting, gives literal meaning to the phrase ‘intestinal fortitude'. Less hazardous is riding a camel along the sands, against a backdrop of an enormous, lurid sun dipping to the horizon.

Bombay has its share of conventional attractions—two outstanding museums, several art galleries and imposing concert halls, for example. But the city's true pulse lies in the rhythm and throb of its streets.